The Western conception of Alf Layla Wa Layla, or The Arabian Nights, or The Thousand Nights and a Night, has been influenced more by its European translators than by the original texts. In fact, there is no definitive original text of this massive work, which has evolved from a variety of sources, some written, some oral, but all of which share the famous frame story of the king’s wife who forestalled her execution by telling a new story each night for 1001 nights, by which time the king fell in love with her and stayed her execution. Some of the more famous tales are not even in the Middle Eastern sources that make up the “1001 Nights,” most notably the “orphan tales” Aladdin and Ali Baba, for which there are no known Arabic originals that predate the first European translations. The European fascination with The Arabian Nights began with the first translations by the Frenchman Antoine Galland (1646-1715) whose versions of the tales appeared in 12 volumes from 1704-1717. Some were translated by Galland and some were related to him orally by Arabic storytellers. The first English version was published in 1706.

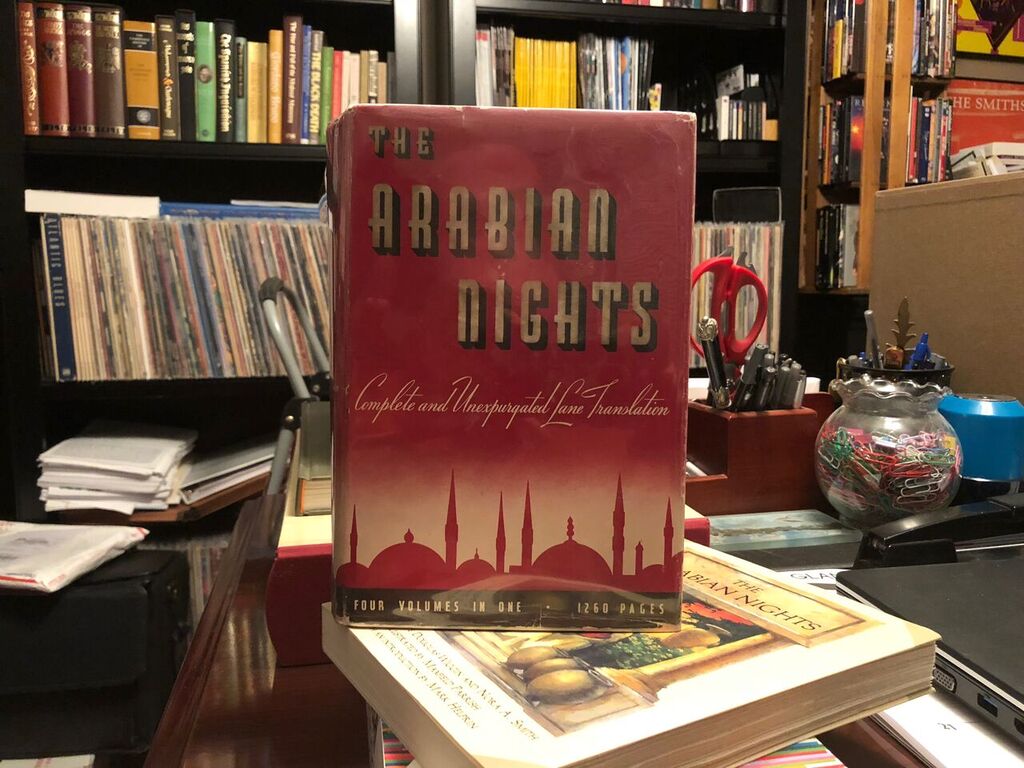

The Dalenberg Library’s copy of the Lane translation of The Arabian Nights is a 1927 edition, which includes the extensive notes and commentaries which were added to the Lane version after the translator’s death. Edward William Lane (1801-1876) published his translation in 1840, with a revision in 1859. This particular edition, from Tudor Publishing Co. , is amusingly subtitled on the dust cover “Complete, Unexpurgated Lane Translation.” The reason that is so funny is that the Lane translation is most famous for being a totally bowdlerized (i.e. expurgated) version of the tales. To read Lane is to get a glimpse of the British Empire’s obsession with Orientalism while at the same time remaining strictly Victorian. Lane’s prose is charming but stifling, as he writes in a mock-Biblical fashion with lots of “thees” and “thous.” He stays true in some ways to the originals (Aladdin and Ali Baba are nowhere to be found in Lane). However, Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890), a better and more complete translator of Alf Layla Wa Layla, pretty much condemns Lane as having no real affinity for the Arabic people and often bungling his translations of the language. You will read commentators today who condemn Burton for over-emphasizing the eroticism of the tales (quite the opposite of Lane) and for being racist (Lane was way more racist than Burton.) The reality is that Burton had great respect and love for the cultures that gave birth to these stories, and he was way ahead of his time on the topics of sexuality and race.

There are newer translations of some of the tales that attempt to erase the influence of the French and British imperialists. However, the most complete version that is firmly rooted in the mind and languages of the Middle East is the Burton version. Lane has long been a favorite of people who wanted The Arabian Nights to be orientalist fairy tales for family consumption–it reads like the Bible, and you can easily distill it down into childrens’ stories. It is Alf Layla Wa Layla as seen through the lens of a Victorian-era British imperialist.